Joyfully Pessimistic: We're not going to be happy, but you do have to laugh about it

This August the city was full of people telling stories of mental breakdown,

environmental collapse and species extinction, political turmoil, repression and even despair.

It was also full of joy.

Even silliness.

BEING SERIOUSLY SILLY

This was the first year that there were more clown shows in the late-night slots than straight standup.

In ‘Palestine Peace de Resistance’ by Sami Abu Wardeh, stories of colonial war and intergenerational trauma were interspersed with hand puppets miming birds and this was far from unusual this year.

“Come for the glitter. Stay for the revolution!” promised the show notes for Midnight at the Palace.

Lets talk about that a second though.

If this was revolution it was an internal one. The world didn’t change at the end of the story. In fact you could argue the Cockettes fail at the end of the story.

There were few stages around the city, or gallery walls that offered much prospect of pending victory.

If we look at Bury the Hatchet, Kinder, and in particular Wild Thing! we see work that is urgent, heartfelt and very conscious of the absurdity that the world has turned out like it has.

Ultimately though these artists and the audiences that love them do not see much prospect of things actually changing in the short term.

In other words, they want to celebrate their heroes and stories with joy, share in the absurdity of it all, but are ultimately pessimistic about the world.

That has big implications for lots of people who want to create movements or brands that drive change.

THE CONTEXT

This shift is not isolated to the artistic world in a narrow sense.

This year in Mara van der Lugt’s book, Hopeful Pessimism she framed much of the modern sensibility as ‘hopeful pessimism’ and even raised the possibility of “pessimistic activism.”

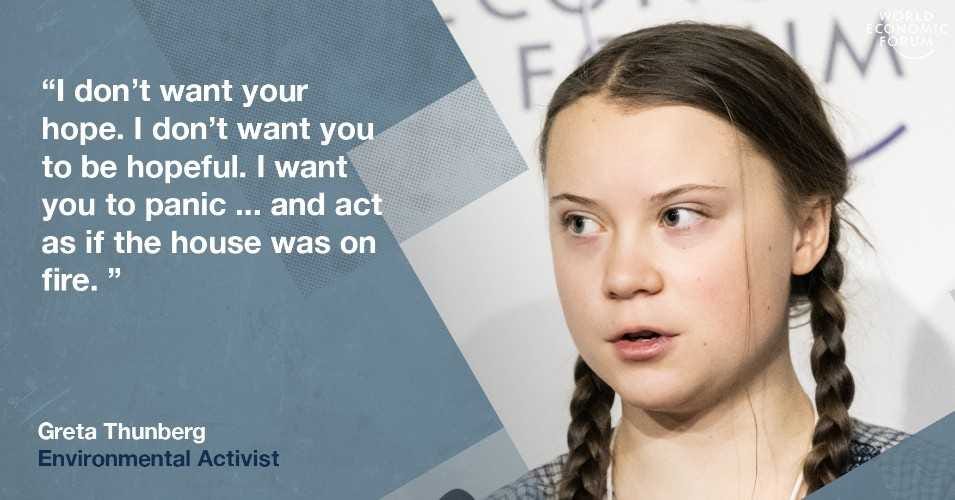

To articulate that she cited Greta Thunberg telling an audience at Davos, “I don’t want your hope” as the ideal case study.

WHAT IT MEANS FOR PEOPLE WHO

MAKE NEW THINGS

For a long time when we have thought about activism we have lived in the brand world of Patagonia i.e. practical people solving the world’s problems with technical solutions.

What do social movements and sustainable brands look like when they are built for pessimistic activists?

What happens when you are talking to people who want to do what we can, but know that won’t be enough?

Judging by Edinburgh this summer, these kinds of brands will need to be very funny. In fact all of this suggests that urgent, radical brands and movements should hold space for a much more playful, joyful, silly way of talking about serious stuff.

But we also need to recognise that excessive optimism can be toxic. Or just irrelevant.

This feels like some kind of new design principles.

Let us also consider one group who will face real challenge though. That is brands and movements designed in more optimistic times.

If you’re BCorp or Patagonia, or one of the OGs of that strain of millennial optimism, then change is going to be hard.